Judith’s Review of Reviews: Arte Joven

Theorists on the magazine as a genre have used various metaphors for the magazine as a test bed for new expressive forms. Beatriz Sarlo has described the magazine as a ‘banco de prueba’, while Margaret Beetham has described the magazine as an ‘enabling space’ and a ‘nursery’.[1] Nowhere can these ideas can be demonstrated more clearly than with the artistic and literary magazine Arte Joven, a magazine created by the young, for the young, as a space for their new, fresh, ideas to germinate. In this analysis of the six remaining digitized issues, from the five issues of first epoch of (10/3/1901 – 1/6/1901) and the second phase of 1909 (1/9/1909), I will show this Modernist magazine, fittingly launched at the crossroads between the centuries, was a showcase for new Modernist writers and artists. Some of these creative men fell into obscurity and failure (in the words of their own erstwhile co-creatives) while others rose to global renown.

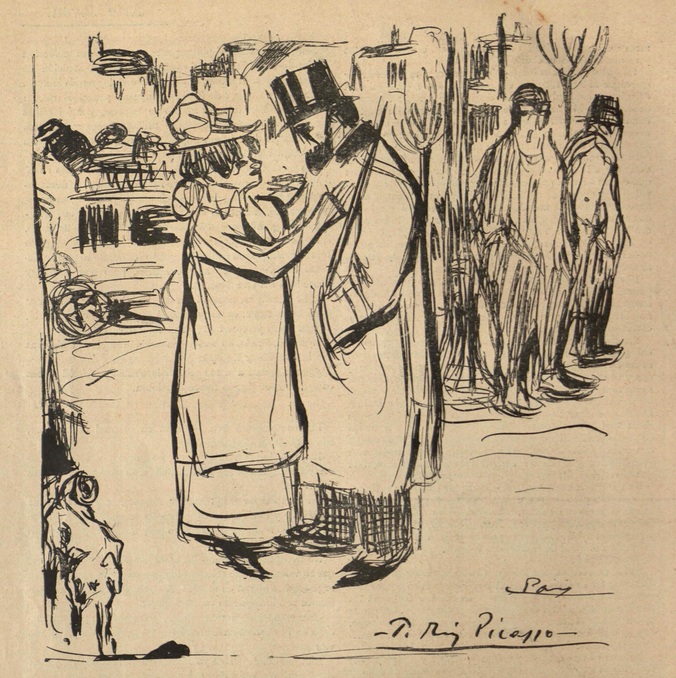

Within the six issues, 43 named contributors can be found, which does not include the names which are listed as future contributors in the second epoch but who do not then appear in this sample. Perhaps because of the magazine’s artistic rather than political focus, there is very little anonymity. Any anonymous writing tends to be news tidbits, likely to be authored by the literary director of the first epoch, Francisco de Asís Soler. The literary director was also the magazine’s most assiduous writer, with six entries under his name, half of these being non-fiction opinion pieces while the other half are short-story fiction. However, the most featured contributor by far to the magazine is the artistic director and co-founder with Soler, an individual known as Pablo Ruíz Picasso, whose etchings and paintings festoon the magazine at every juncture. When in a study of six magazines, five of which were only eight pages long (and the eighth page being generally given up to advertisements), it is fair to say that with 26 scenes of Spanish (particularly Madrid) life, Arte Joven is especially a showcase for this artist’s talents. Even the magazine’s title itself becomes one of his works of art from issue 2 onwards.

(Note that issue 2 was the only issue in which colour was used in any way – the choice being arsenic green.)

While Picasso did predominate in terms of the graphic art, other artists and writers do feature in the magazine. Of the original language contributions, Camilo Bargiela, Pío Baroja, Pedro Barrantes, Ramón de Godoy y Sala, Bernardo González de Cándamo, José Martínez Ruíz (later known as Azorín), Juan Gualberto Nessi, Alberto de Lozano and Miguel de Unamuno all contribute more than once. Pío Baroja’s brother, the painter Ricardo, contributes with three charcoal studies of Modernist friends. There are also one-off contributions from foreign authors, who appear in translation. Germany is represented by Goethe and Schiller, England by Shelley, Portugal by Guerra Junqueiro, and Catalonia by Santiago Rusiñol and Jacinto Verdaguer, whose translations, we have been told, have been done expressly for Arte Joven (although with translators’ names not stated, we can assume that translation was seen as a transparent, unproblematic and unartistic process).

The magazine has a strong commercial bent, with many adverts for the contributors’ books for sale, books which are also promoted through the publishing of excerpts within the magazine, whether these be textual (Emilio Fernández Vaamonde, Pío Baroja) or graphic (Picasso). There are also reviews/promotions of contributors’ books (José Martínez Ruíz, González de Cándamo, Pío Baroja, Ramón de Godoy y Sala) and portraits of eleven of the contributors all work to give the sense of a tightly-knit community. That said, the magazine (on behalf of its ideal readership) also looks to foreign shores, with publisher Rodríguez Sierra of Madrid choosing this new magazine’s first issue to advertise its books from writers such as Schopenhauer, Emerson, Nietzsche, Ruskin, Kropotkin, Sienkiewicz and Merejkowsky. There is also a music review for Wagner, a book review for Pedro César Dominici, and a list is published in 31/3/1901 in which, of the nine magazines with which Arte Joven has established an exchange, two are French and one Portuguese.

The magazine’s mission statement betrays the confidence of the young and energetic, without straying into unfounded arrogance. Their mission is to renew, to ‘regenerate’, but without disrespecting the greats who have gone before. An excerpt:

Sin compromise, huyendo siempre de lo rutinario, de lo vulgar y procurando rompe-moldes, pero no con el propósito de crear otros nuevos, sino con el objeto de dejar al artista libre el campo, libre completamente para que así, con independencia, pueda desarrollar sus iniciativas y mostrarnos su talento.

No es nuestro intento destruir nada: es nuestra misión más elevada. Venimos á edificar. Lo viejo, lo caduco, lo carcomido ya caerá por sí sólo, el potente hálito de la civilización es bastante y cuidará de derrumbar lo que nos estorbe.

Lo que subsista, lo que tenga fuerza suficiente para resistir los embates de lo nuevo, lo que se mantenga firme é incólume, á pesar de la tormenta, no es viejo: es joven, joven siempre, joven aunque cuente mil años de existencia.

Virgilio, Homero, Dante, Gœtte [sic], Velázquez, Ribera, el Greco, Mozart, Beethoven, Wagner… éstos son los jóvenes eternos, cuantos más años pasan más grandes son, crecen en vez de perecer y mientras el mundo exista existirán ellos: Son los inmortales. (10/3)

They also have the confidence to define themselves in terms of who/what they are not, as they make clear in the Notas sections:

Cuando se publicó Gente Vieja D. Eusebio Blasco declaró que se creía joven para pertenecer á aquella redacción.

Nosotros declaramos que no puede pertenecer á la nuestra por conceptuarle demasiado añejo.

De modo que el amigo de proceres y de emperadores actualmente en literatura está… suspendido en el espacio como el alma de Garibay. (10/3)

¿Cómo les gusta á ustedes más Saint-Aubin, pintando ó escribiendo?.....

A nosotros de ninguna manera. (10/3)

Nuestra revista no publica retratos, biografías, ni necrologías de toreros.

A pesar de ser un periódico de Arte, conste que nada tiene que ver con el noble arte del toreo. (10/3)

Sabemos que á los encandilados gomosos madrileños y á las ilustradas señoritas de la aristocracia, no les ha gustado ARTE JOVEN. Esto, que parece tendría que contrariarnos, nos satisface inmensamente.

No podemos ser simpáticos, de ninguna manera, á los lectores asiduos de Blanco y Negro y á los coleccionistas de cromos de las cajas de cerillas. (31/3)

The editorship do make clear however, that they will be very kind to readers who make unsolicited contributions, or who send in books to review:

ARTE JOVEN, acusará recibo de los libros que se sirvan remitirnos.

¡La Casa no ha escogido todavía críticos!

Pero, compasivos, casi nunca trataremos con dureza á los autores.

Harto trabajo tiene quien publica un libro en nuestro país. (10/3)

De los trabajos que se sirvan remitir los colaboradores expontáneos [sic], daremos nuestra humildísima opinión, amados hermanos.

¡Dinero! No daremos!

¡Pero Gloria sí! Toda la que querais y la escasa parte que á nosotros pueda correspondernos. (10/3)

Perhaps this last encouraging message, humorous in tone, was inserted exactly because not all magazines were positive about unsolicited contributions which were sent to them, as shall be made clear in the upcoming review of the magazine Luz (1898).

However, the enterprise, for all its confidence and grandeur, does not last long, ending after only five issues. Perhaps Picasso, the driving force behind the title, had decided that it had served its purpose within his own life.

The magazine is reborn in on the 1st September 1909 with a new editor, F. de Sorel - Francisco de Asís Soler having since passed away. The roll-call of writers reveals a new team, although ghosts still haunt the production, with a chapter of Soler’s unpublished book being featured, and old sketches of Picasso being used to decorate the pages. Two of these sketches selected are of Soler and Picasso himself, by way of honouring those who have gone before. The new team in Barcelona make it clear in their editorial that their mission is to continue the work of the old team in Madrid, and to this effect they publish the original mission statement in full. The magazine, while now in landscape orientation and double the number of pages, maintains Picasso’s original cover/title artwork. It is clear that ‘otras firmas figuran en él, pero el espirítu que lo inspira, el alma que lo anima es la misma.’

As if to heal the breach between the two epochs, the editor invites the writer Emilio Ramírez Ángel to write at length (almost two pages) about the first epoch and how the ravages of the intervening eight years have affected the original team. An excerpt:

Francisco de A. Soler y Alberto Lozano han muerto sin cejarnos la obra definitiva que innegablemente hubieran producido. […] Descansen en paz los primeros apóstoles y caiga sobre ellos mi piedad y mi simpatía.

A Ramón Godoy y Ruíz Picasso — dibujante este ultimo de una inquietud ópima, de un lápiz indómito y seguro — no he vuelto á verlos ni nada sé de ellos. Creo que Picasso triunfaba hace años en París; en cuanto á Godoy me parece haberle visto una noche por este Madrid luciendo su flexible negro y su media melena romántica.

Cuatro bajas.

Camilo Bargiela empezó haciendo un libro humorístico y grato titulado, si no recuerdo mal, Luciérnagas y ha acabado retratado en Nuevo Mundo como Cónsul en Casablanca. Pero nada he vuelto á leer suyo ni ningún adorable compañero me habla mal de él.

Y van cinco.

Ricardo Baroja presenta alguna vez alguna aguafuerte en alguna Exposición. Por lo demás suelo verle con frecuencia en el café de Levante, y no sé si toma café con media y con Valle Inclán. Charla mucho.

Creo que van seis. Seis bajas.

He then goes on to talk at length about Bernardo G. de Candamo, of whom he says: ‘Candamo debe de tener talento, aunque no lo aseguro. Sé que alguna vez vende los libros que le dedican, y que murmura bastante. No quiero considerarle aún como fracasado’. He is then extremely scathing about José Martínez Ruíz, who has turned his back on his old friends to become part of the conservative political establishment:

Martínez Ruíz, el admirable prosista de La voluntad y Los pueblos, ha muerto. Probablemente resucitará como gobernador de una provincia de tercer órden, si Maura no dispone otra cosa. Muerto Martínez Ruíz — y van ocho bajas —el Azorín ministerial nos tiene sin cuidado. Toda su rica literatura ha ido á parar á un escaño. ¡Y pensar que á este señor diputado por Perchena le mandó detener en Ontaneda, como anarquista presunto, el señor Maura!...

He then turns his attention to the final member of the old redaction who is yet to be assessed. To further ironize his assessment in light of the events subsequent to his time of writing (and perspective) I have put section of the text in bold:

Pío Baroja es el único que se destaca, vivo y triunfal, de todo este montón de cadáveres. Sigue siendo una especia de ciprés al borde de tantas sepulturas. Baroja es uno de nuestros novelistas mejores. Su desilusión y su humorismo le han forzado á engendrar páginas que repute admirables. Pero no olvideis que cuando apareció ARTE JOVEN, Baroja había publicado ya su libro Vidas sombrias (1900) y que, por consiguiente, era ya entonces also más que una esperanza.

Ocho nombres, ocho, y de ellos uno solo en pié. Ausentes, fallecidos y fracasados los demás. ARTE JOVEN hacían en 1901… Hoy, ya lo veis: era necesario que ARTE JOVEN renaciera con nombres nuevos, de creciente prestigio como Sorel y los que le acompañan. Procurad pues que, á la vuelta de otros diez años no venga otro mozo que, como yo, pase revista á la flamante redacción de hoy y la encuentre tan derrotada y reducida como la de antaño.

This is a particularly important passage, because it highlights the reality which our project seeks to demonstrate further, which is the fallacy of using modern eyes to look at the past and make assumptions about the perception of an individual’s merits through the lens of his subsequent canonization or rejection, by assuming that his contemporaries will have judged him to be as great, mediocre or unworthy as he is considered at our point in history. Equally, it is tempting to look at a magazine and the nature of the social network formed around that magazine through the bias of our current historiography, and arrive at assumptions about how the writer would be connected to other writers, again, because of critical fame, notoriety or neglect in subsequent years. This passage, more than any other, which sees Picasso as just another failure, is a wonderful example of how, to thoroughly uncover the reality of how historical events and people actually were, one must go ad fontes, with a methodology as empirical and distant (i.e. free from conscious or unconscious prejudice), as it is possible for a human being to create.

[1] Beatriz Sarlo. ‘Intelectuales y revistas : razones de una práctica’, América : Cahiers du CRICCAL, n° 9 -10, 1992 (p. 11). Margaret Beetham. ‘Towards a Theory of the Periodical as a Publishing Genre’ in Lauren Brake (ed.), Investigating Victorian Journalism. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1990 (p.25).

Comentarios

nanette

Jue, 10/12/2017 - 12:04

Enlace permanente

Arte Joven - revista contradictoria

Dear Judith,

I would not overestimate the role of Picasso in the publication of Arte Joven: He was already living in Paris in 1901 and probably sent his gravings and drawings by mail to Soler in Madrid. But thinking about Paris and Madird, this is another international network, that might be interesting for you.

See also my article on Arte Joven (you probably know):

The paradoxes of Arte Joven: high and low culture before the rise of the avant-gardes

judith.rideout

Sáb, 10/21/2017 - 14:29

Enlace permanente

Reply

Hi Nanette, I based my thesis of Picasso's leading role in the direction of Arte Joven on the article, available online, by Francisco J. Flores Arroyuelo, 'ARTE JOVEN: 1901, una revista modernista' (Monteagudo, 3a. Época - No 7, 2002, págs 23-30), which states that Picasso's studio in Madrid (c/Zurbano) served as the magazine's office. Given the magazine's short lifespan of five issues (10th March - 1st June) I think it is likely that Picasso played a central role throughout this time, even if he may have nipped away to Paris once or twice. And thank you for the link to your article - I will read it now with great interest!