Judith's Review of Reviews: Luz

It cannot be argued that the magazine Luz was designed to be an aesthetic commodity, a magazine of an artistic and writing collective which had as its aim the inspiration of whoever picked it up. The magazine’s first epoch began on the 15th November 1897, with a fortnightly publication which cost 10c. It is unclear when the first epoch of the magazine ended, but this may have been with the 31st January 1898 issue, the last extant issue of this epoch, because an urgent appeal for overdue monies from subscribers, found on the second page, suggests a cashflow crisis (‘Los señores corresponsales que no hayan liquidado antes del 15 de Febrero, no recibirán más nuestro periódico’). The second epoch of the magazine began eight months later, on the 7th October 1898, with the magazine now being weekly, and the price increased to 15c. This article is an overview of Luz based on the extant issues held by the Biblioteca de Catalunya, available to view at Arca: Arxiu de revistes catalanes antigues (www.bnc.cat/digital/arca). These issues comprise the unbroken first epoch and second epochs, which span the dates 15/11/1897-31/1/1898 and 7/10/1898-29/12/1898 respectively.

The magazine is initially printed in solely black-and-white print, a monochrome which greatly limits the effectiveness of the artistic reproductions, and it is clear that this is something which the editors seek to change, as issue 5 of the first epoch (15/1/1898) introduces the innovation of front and back covers in arsenic green (also found in later issues 15/10/1898 and 22/10/1898). The innovations continue when in 7/10/1898 and 15/11/1898 the front covers are in a warmer shade of black than the rest of the magazine, and the entirety of 7/11/1898 is printed in a monochrome of an interesting pinkish-brown (see image above). A bright brick red begins to appear in elements of the front covers in the latter half of the second epoch, front covers which are themselves works of art.

An extract of the anonymous editorial mission statement of the first issue gives a fair idea of what will be found in the magazine, and the editorial priorities:

Nos lanzamos á la publicidad con muchas aspiraciones, mucha fe y mucho entusiasmo.

No pretendemos crear nada nuevo, porque en este siglo se va haciendo difícil la inventiva, pero sí ser el portaestandarte de todo lo nuevo, y al decir esto, queremos indicar de todo lo que tienda á abrir nuevos horizontes al arte y á la literatura.

No seremos políticos. Odiamos lo inmoral, y la política no es más que un cúmulo de inmoralidades.

No seremos filósofos. La filosofía, con sus divagaciones, consigue tan sólo hacer dudar.

El carácter que imprimimos á nuestra publicación, es sólo el literario-artístico, y teniendo en cuenta que, á pesar de nuestros esfuerzos y buena voluntad, sería poco lo que conseguiríamos, pues que pobre ha de resultar siempre nuestro trabajo, nos hemos procurado la cooperación de elementos importantísimos, tanto artísticos como literarios.

Podemos asegurar, por lo tanto, que en nuestra revista colaborarán distinguidos escritores y aparecerán ilustraciones de reputados dibujantes nacionales y extranjeros.

Indeed, true to their mission statement, unlike other magazines of the period (e.g. Germinal, Vida Nueva, Gente Vieja) there are no political articles and only two articles which expound on a theme in an encyclopaedic fashion. The expository articles in question are a serialised history of musical instruments, and a history of the play Ifigenia. The long text of both articles is interspersed with many illustrations. The only other non-fiction to be found is profiles of creative luminaries (always accompanied with illustrations/photographs); reviews, mostly of the theatre, and snippets of cultural news, which are always kept short and sweet. True to their word, the editors omit the (often long and tedious) ‘philosophical’ writing found in many other magazines of the period (e. g. Germinal, Gente Vieja). As might be expected in a publication which appeared to have been conceived to stir the imagination, lots of space was devoted to fictional prose and poetry. There was not the ‘wall-of-text’ that characterized other magazines of the time (e.g. Vida Nueva, Gente Vieja) making the magazine easy on the eye and an attractive proposition to browse. Like their (almost) contemporaries in Madrid with their Arte Joven, the collaborators at Luz focus on the latest Modernist tendencies of art, but like Arte Joven also profess a passion for the great creatives of the past, with El Greco and Goethe lauded in both titles.

This is a magazine which is arguably more about the artistic aspect of Modernismo as the textual side, if not more so, and this is borne out by the magazine’s subtitle, ‘Arte Moderno’. The magazine features visual reproductions of all forms of cultural artifacts – musical scores, woodcuts, book/magazine illustrations, book plates, paintings, sculpture, advertising posters, cartoons from foreign magazines, photographs of famous people and theatrical scenes, magazine covers and theatre bills. It is also rich in the graphic design elements around texts that have become standard in modern magazines, and much of the art experiments with different elements and styles (see the cover of issue 2, above). The love of the aesthetic infuses every corner of the magazine, to the point that not only article titles become artworks in themselves, but even adverts can be seen as miniature works of Modernist art.

There are over 100 identifiable contributors to the magazine, as the identity of a large number of contributions which are anonymous or signed with initials only cannot be ascertained. The magazine’s texts are written in both Spanish and Catalan, although mostly in Spanish, with 28 elements of the magazine written in Catalan as opposed to 186 elements in Spanish. Editorial writings – news snippets, correspondence etc. – are always in Spanish.

The most regular identifiable Spanish/Catalan contributors to the magazine are for the most part multi-modal in their forms of expression, many of the writers combining their talents in writing, using all genres (non-fiction and fiction prose, reviews and poetry) and art (painting, drawing and photography). These writers are: José María Roviralta (poetry, prose and art), Joan Gay (prose and musical scores/lyrics), Eduardo Marquina (poetry), Francisco de Asís Soler (prose and poetry), Alexandre de Riquer (prose and art), Dario de Regoyos (art), José Pichot (photography), Adriá Gual (poetry and art), Isidro Nonell (art), J. Joaquín Nin y Castellanos (prose), Santiago Rusiñol (prose, poetry and art) and Angel Cuervo (prose). In addition, there are also three female contributors found within the magazine: Marian Roig who contributes two poems in Catalan, Rosalía Castro de Murguía, whose (Galician) poem Follas Novas is posthumously reproduced in translation into Catalan, and an illustration from English artist Eleanor Fortescue-Brickdale (pictured).

An editorial note in 22/10/1898 states that Luz has a very clear policy with regards to originals, translations and the authorization for reproduction of work, although given the wide variety of reproductions, one must assume that they are referring to living, Spanish contributors in this instance:

Ponemos en conocimiento de nuestros lectores que todos los trabajos que publica este periódico han sido hechos ex profeso para el mismo, ó bien el autor nos ha autorizado para reproducirlos. Los artículos de autores extranjeros son también traducidos expresamente para LVZ [sic].

Indeed, perhaps because the translations were translated expressly for the magazine, most come with the name of the translator(s). E. Moline i Broses translates Gabriel Vicaire from French to Catalan, Dario de Regoyos translates Émile Verhaeren from French to Spanish, and the translating team Eduardo Marquina and Luis de Zulueta translate both French (Paul Verlaine) and German (Johann Richter) into Spanish.

The magazine also makes good its promise to reproduce illustrations from renowned foreign artists, as work of artists and writers from all over Europe is reproduced.

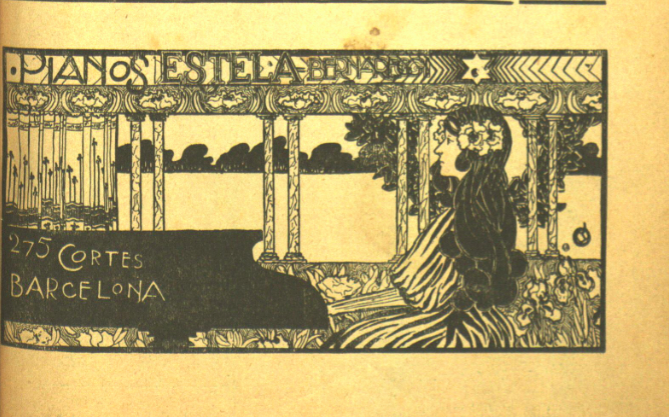

As may be expected, France is particularly heavily represented in the artistic reproductions, with work from Henri Bellery-Desfontaines, Louis Oury, Henri Thiriet, Georges Rochegrosse, Jules Chéret, and Eugénie Grasset. However, it is French artist Pierre Puvis de Chavannes who is the most favoured artist, with nine works featured in the magazine. British art is the next most popular, with English artists Eleanor Fortescue Brickdale, Sidney Meteyard, William Nicholson, Bernard Sleigh and Heywood Sumner having their work featured, while Scottish artist William Brown Macdougall has three examples of his illustrations printed. German artists are next in line for representation, with work from Josef Berchtold, Hans Christiansen and Oskar Zwintscher. Switzerland is represented twice, with artists Carlos Schwabe and Théophile Steinlen. Finally, we see influences from Belgium (Théo van Rysselberghe), Peru via Paris (Albert Lynch), Moravia/Czech Republic (Alfonse Mucha, featured twice) and Norway (Edvard Munch, with a theatre bill of Peer Gynt, pictured).

Foreign writing is also featured extensively, almost as much as foreign art. Again and unsurprisingly, France leads the way with Auguste Germain, Alexandre Hepp, Victor Hugo, Marcel L’Heureux, René Maizeroy, André Chénier, Paul Verlaine, and Gabriel Vicaire. Germany follows close behind, with writing from Johann Paul Friedrich Richter, Heinrich Heine, Ludovico Klein, Friedrich Wilhelm Krummacher and Ludwig Uhland. Other nations’ writers which feature are England (William Makepeace Thackery), Belgium (Émile Verhaeren), Italy (Guy Anatole Catrei) and Russia (Leo Tolstoy).

The magazine also publishes unsolicited contributions from readers, as is demonstrated by the Correspondencia section which features in issues 3, 4 and 5 of the first epoch (15/12/1897 – 15/1/1898). This section comprised a total of 20 replies from the magazine to hopeful readers who had sent in their creative efforts, and reveals not only a candid relationship with readers, but also gives an insight into what the editors were looking for.

For example, the correspondence section showed the editorial attitude to writings in the Catalan language. Although the magazine did publish writing in Catalan, it was clearly with some caveats:

Abeve: Barcelona – Agradecemos muchísimo su composición; pero hemos decidido no publicar trabajos en catalán, exceptuando los firmados por escritores muy conocidos. (15/12/1897)

The magazine staff also made clear that they were not fans of very long or incomplete texts:

R. de S. Y A.: El Busto. – No podemos formarnos idea de su trabajo, porque está incompleto. Mande usted la segunda parte de su artículo, y miraremos de publicarlo. Lo recomendamos sobre todo la brevedad, pues somos muy enemigos del se continuará. (31/12/1897)

In addition, as has been previously stated, the originality/authenticity of work was so important to the magazine, that the administration wanted proof of the work’s authenticity and details of the author’s full identity:

Un suscriptor: Soneto – No admitimos trabajos anónimos. Además, y perdone usted, dudamos de la originalidad de su soneto. Si usted puede probarnos que es suyo solamente, procuraremos publicarlo. (15/12/1897)

M. P.: El primer latido. – No podemos admitir trabajos anónimos. Queremos editor responsable en todos los escritos; por lo tanto, esperamos el verdadero nombre de usted (aunque si quiere no constará en el periódico) y el domicilio. (31/12/1897)

The magazine staff were also quite keen to meet the readers/contributors in person in order to verify their identity, and also to discuss texts with a view to readying them for publication:

Un suscriptor: Soneto. – Referente á su celebérrimo soneto, no dudamos que sea original de usted; pero no quedamos del todo convencidos. Si manda usted la firma bajo su responsabilidad, lo publicaremos. Desearíamos verle por este redacción, pues como comprenderá, no es natural que nosotros le visitemos en su casa. (31/12)

Abeve. – Suplicamos á V. pase por esta redacción si desea ver publicada su historia geroglífica. Es necesario arreglar algo en el texto. (15/1/1898)

However, perhaps the most interesting aspect of the public replies to would-be contributors is the candidness with which the editor(s) assess the writers’ work. The responses range from a brutal honesty which would upset most writerly sensibilities….

O. R. S.: El cielo negro – «Cuando cae la tarde; cuando negras nubes enlutan el cielo»… probablemente lloverá. Así empieza su «Cielo negro», y en verdad que muy negro es y muy obscuro, porque nosotros no hemos sabido ver un punto claro. Cultive un poquito más la literatura, y procure escribir, si no con bella forma, con sentido común. (15/12/1897)

J. P.: Mis deseos. – Apreciable señor: tengo el sentimiento de comunicarle que no puedo hacerle el honor de publicar su composición, porque por más que la he releído, no he sabido encontrarle la punta. (31/12/1897)

A. G. Diciembre. – No podemos complacer á Vd., porque su composición (¡y no se ofenda!) es muy mala. Además, me atrevo á aconsejarle estudie V. de poquito la ortografía, pues por la muestra no está V. muy firme en ella, que digamos. (15/1/1898)

…to what can only be described as downright rude. Even taking into account different social norms across time and space, it is hard to believe that these comments would not be considered offensive to the recipient:

A. C.: La cáscara amarga. – ¡Asómbrese usted! Leí todo su artículo, y quedé anonadado. Probablemente deliraba usted cuando escribió aquellas sandeces. No se meta á escritor, que por lo visto no es ese su sino. Teniendo tanta afición á las ensaimadas, creo que el oficio más acertado es el de pastelero. (15/12/1897)

Un Luz. Protesta. – Es V. muy guasón, amiguito, pero guasón con poca sombra y menos gusto. No ha nacido V. para ser poeta. ¡Quizás sería V. un buen zapatero! Hay mucha gente que no sabe lo que le conviene. (15/1/1898)

Amusingly, the correspondence section ends after the fifth issue, perhaps because aspiring writers and poets feared the scathing responses to their efforts that had been seen in previous issues. What is certain however is that the magazine more than enough art and literature to display on its pages, which makes Luz a treasure trove for the researcher with an interest in the influences of entresiglos Spanish Modernism.