Judith's Review of Reviews: Vida Nueva

Fittingly for what it was to contain, Vida Nueva began on the 12th of June 1898 just as the Desastre del 98 was unfolding, in which the last of Spain’s significant colonies were lost to the United States.[1] The weekly newspaper soon came to epitomize the spirit of the Generación del 98, the writers, artists and thinkers who sought to critique Spanish society and rebel against the established traditions, mentalities and aesthetics which had led to Spain’s current lamented state. This new generation looked to modernism and beyond Spain’s frontiers for inspiration on how to ‘regenerate’ Spain for the 20th century, and while it was committed to being ideologically open-minded to maximize the potential for good ideas, the newspaper irreverent anticlericalism soon became undeniable. Its circulation was also significant, with a circulation of 40,000 weekly copies by issue 4 (3/7/1898) announced for the information of potential advertisers.

Although the newspaper lasted for 94 issues until March 1900, this is a study of the first ten copies of the newspaper held by the Biblioteca Nacional de España and found in their hemeroteca digital, which corresponds up until the 14 of August 1898 issue.[2] Any commentary made about the newspaper after that date are taken from Celma Valero’s study of the newspaper (see previous footnote).

Vida Nueva’s appearance was very much that of a traditional newspaper, that is, taking a large broadsheet format with lots of articles in small newsprint packed closely together. There are no images in this newspaper during the first ten issues, except for a comedy map of Spain in 10/7/1898 whose purpose is more satirical commentary than artistic (pictured below). However, graphics and photographs do appear in later issues, with photographs notably used in the newspaper’s controversial coverage of the Montjuich trials, while most drawings and etchings come from Apeles Mestres. Almost all of the newspaper’s text is in Spanish, perhaps mindful of the newspaper’s Madrid-based staff and its primarily sociopolitical focus. The two exceptions to this are a non-fiction prose commentary by Santiago Rusiñol published in the original Catalan (‘Fulls d’Art’, 10/7/1898), and an anonymous report on Vida Nueva being reviewed in the New York Herald with the original paragraph in English being reproduced faithfully within the report (26/6/1898).

Within the first ten issues, there are a total of 105 identifiable authors. As might be expected for such a contentious newspaper which attracted official complaints and Church censure, there is a great deal of anonymity, and articles are often signed with a cryptic initial or initials if anything at all. The most assiduous writers of those named are Eusebio Blasco (unsurprising, given that he was its founder and first director), Vicente Blasco Ibánez, Manuel Bueno, Juan José Cadenas, Mariano de Cavia, José Verdes Montenegro, Miguel de Unamuno, Felipe Trigo and Salvador V. de Castro. Other prominent domestic names are Joaquín Alcaide de Zafra, Vital Aza, Federico Balart, Ernesto Bark, Francisco Bulloes, Ramón de Campoamor, Antonio Cánovas de Castillo, José de Casanave, Emilio Castelar, Luis de la Cerda, Vicente Colorado and Francisco Fernández Villegas (‘Zeda’). Only one woman’s by-line features in this ten-issue sample, that of Brígida M. Caamaño, who writes a letter to the editor in 3/7/1898, but several women do appear in later issues (most notably, Emilia Pardo Bazán).

The foreign authors represented are primarily French, with a range of work reproduced in translation from Jean de Bonnefon, Émile Zola, Alexandre Dumas, Édouard René Laboulaye, Gustave Nadaud and Hippolyte Taine. Italy is represented with two translated poems from Gabriele D’Annunzio and Giacomo Leopardi, while Germany is represented by a Heinrich Heine poem. Interestingly and anachronistically, a poem by ‘Al-Ashjai’ of Cordoba is also found under the title ‘Poesías arábigo-hispanas’, translated by Rodolfo Gil. While Norway’s Henrik Ibsen does not feature as a by-line, he is profiled by Eusebio Blasco, who reproduces part of an interview with the playwright, which quotes him at length.

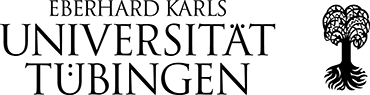

By far the most dominant genre of the newspaper is non-fiction prose commentary, giving the opinion of the writer. Often these pieces are critical – of the government, of the judiciaries, of the parliamentary system, of the universities, of the Church, of Spain; all of the institutions which could conceivably come under the philosophical purview of a regeneracionista. Some articles are numerical breakdowns of government and other spending, to highlight the calamitous financial situation of the country. But the newspaper also featured poems, short stories and sketches in abundance.

However, it was the satirical swipes at the Church, whether it be with serialized fiction (‘Jesús: Memorias de un jesuita novicio’, Dionisio Pérez, 24/7/1898 onwards) or spoof canonical epistles from St. Anthony (‘Escribe San Antonio’, Francisco Bulloes, 31/7/1898) that would draw most ire from institutionalized power, here the Catholic Church. In the 7/8/1898 issue there is a notice that the Archbishop of Seville, by means of a circular which has been read out in all the churches of the diocese, has recommended to the parishioners that they no longer read Vida Nueva. The notice having only been received when the issue in question was going to press, readers are assured that they will receive a reply to this sanction from the editor Eusebio Blasco in the following issue. In fact, the following issue (the last issue of our sample) contains a number of replies to this matter, with Blasco’s well-considered and temperate reply being the leading article on the front page. In addition, the archbishop’s uncharacteristically diplomatic missive is printed in full at the start of Blasco’s response, leaving the reader to judge who is the winner in this debate of rhetoric and ideas. Less polite is the response to the bishop from pseudonym V. Hugo on the same page (‘Al Obispo que me llama ateo’), while ‘P. Q.’ in the same issue comments on the absurdity of excommunicating a newspaper in ‘Confundir las especies’, even though the archbishop’s original missive did not talk of excommunication despite (according to Blasco himself) this being reported as such in the press. Eusebio Blasco also responds to the news that another archbishop, this time of Tarragona, has followed the Archbishop of Seville’s lead in instructing his parishioners not to read Vida Nueva, and Blasco, who proclaims himself a Christian in his headline article, wonders aloud if this is the beginning of an ecclesiastical campaign against his newspaper. Nevertheless, he remains defiant that he will always have an audience:

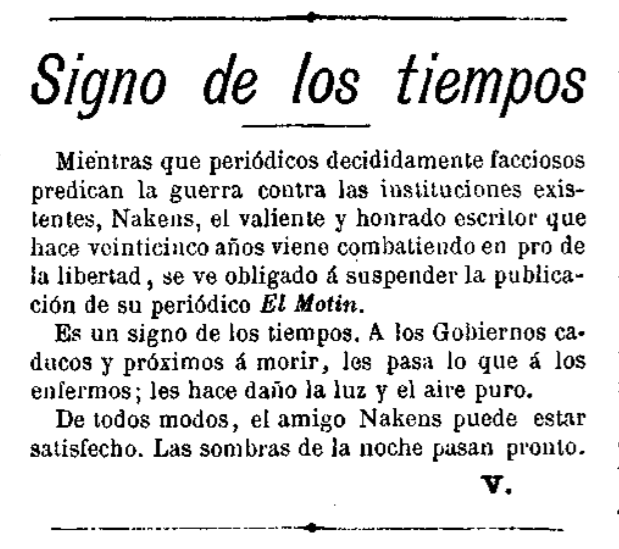

However, it is a short article in this same issue, the final newspaper of the sample, that suggests that Blasco’s battle for the free expression of ideas is only just beginning. ‘Signo de los tiempos’ tells of José Nakens periodical El Motín being suspended. While one could may be some merit in the anonymous writer’s comparison of outdated, dying governments being like the infirm who are hurt by sunlight and fresh air, his assertion that ‘las sombras de la noche’ would soon pass was at best a platitude. As history would come to show, political censorship and institutional opposition would be around to plague Nakens, Blasco and their fellow freethinking journalists for many years to come.

[1] I say ‘significant’, because history books tend to forget about the continued existence of Spain’s African colonies when they state that Spain lost the last of its colonies in 1898.

[2] The information about the newspaper’s total run comes from María Pilar Celma Valero’s Literatura y Periodismo en las Revistas del Fin de Siglo: Estudio e Índices (1888-1907). Madrid: Ediciones Júcar, 1991 p. 43.