Teresa Herzgsell: Categorization as Theory and Practice: Type of Contribution

The system that we created to collate the data extracted from the magazines (see Teresa Herzgsell Categories) includes a typological system for the magazine contributions designated ‘Type of Contribution’. We decided on a typology rather than a classification, as a typology allows for the overlaps and liminality in categorisation (Müller: 21) that reflect the reality of our historical material more accurately. We developed seven categories for the magazine contributions: Lyricism, Fictional Prose, Drama, Review, Magazine Review, Non-fictional Prose, and Image. The overarching goal of sorting the contributions into these categories falls in line with the typical goal of any typology, which is ‘to gain an overview of the order within the diversity of the phenomena within an object area’ (1) (Lehmann) (2).

In order to explain this typological model, we need to return to the classical literary genres of antiquity. This is necessary because of the fact that the principal categories for literary texts in our corpus are derived from the classical genre distinction: Lyricism, Epic, and Drama, (3) albeit the term Epic has been replaced by Fictional Prose in our model. This triad has been in place for so long in Western culture that it has become the totalising paradigm for many, and as such, is liable to appearing irrefutable. This is not our understanding of the genre; we view it as a terminology (Fricke: 7) that has been socially constructed and therefore can be developed and revoked where necessary. The following paragraphs, therefore, illustrate a more fluid understanding of the genre as a typology, that informs the principles behind our categorizations, and reflects back on our practice of completing the datasheets as well as the suggested handling and reading of the data gleaned.

As John Frow argues, there is a general misjudgement regarding literary taxonomy. It has often been described in analogy to other forms of taxonomic operations in biology or chemical studies (Frow: 56 f.). Those taxonomies are generally unambiguous and require a certain consistency, uniqueness, and completeness. Requirements, however, that cannot be fulfilled in any ‘real-world’ system because, as Frow argues, ‘in every system principles are mixed, and there are anomalies and ambiguities which the system sorts out as best it can’ (Frow: 56). This is especially true for the genres of literature, since they are ‘facts of culture, which can only with difficulty be mapped onto facts of nature’ (Frow: 58). As such ‘facts of culture’ they are not subject to the same restrictions as ‘facts of nature’, and can be intermixed. Moreover, every text has repercussions on the group of texts that constitutes a category, making them constantly changing and fluid concepts (Frow: 58).

This, for Frow, is reason enough to reject the analogies drawn between the taxonomies in natural sciences and those in cultural or, more specifically, literary studies. In search of a better-suited approach he turns to ‘models of classification [that] seek to address the fuzziness and open-endedness of the relation between texts and genres’ (Frow: 58). One of those models is the idea of a prototype-based model, where categories are based on similarities between a constituting text and other text that can be attributed to the same group based on those similarities. In the end, however ‘[t]he judgement we make (“is it like this, or is it more like that?”) is as much pragmatic as it is conceptual, a matter of how we wish to contextualise these texts and the uses we wish to make of them’ (Frow: 59). And this is exactly where our approach falls in one with that of Frows. We agree with his opinion that ‘in dealing with questions of genre, our concern should not be with matters of taxonomic substance […] to which there are never any ‘correct’ answers, but rather with questions of use’ (Frow: 60). To phrase it in respect to the title of this article, for us, categories are a decision, not a paradigm.

This article, then, is to explain to what end we developed our system of categories, and how they are constructed. We do not claim that the organizational chart we include as a visual support below is in any way complete, or that it addresses the fluidity of typological operations, but ask that it be viewed in the light of our desire to make the conception and composition of our categories as transparent and comprehensible as possible. We encourage the perception of these categories as a system that is useful to our research, a system that may have to be adapted to meet the requirements of further research with the material.

There is another point that needs to be made regarding our datasheet classification system, and it is one that brings to mind Derrida’s The Law of Genre, because it concerns the cross-contamination of genres. Derrida puts it in an interesting way, when he states: ‘a text cannot belong to no genre, it cannot be without or less a genre. Every text participates in one or several genres […]’ (Derrida: 65). This is an observation that needs to be specifically stressed when it comes to our historical materials. In sorting the material into the categories we developed, it became more than obvious that not just the establishment of categories but also the decision to put a generic label on a concrete contribution is problematic. The reason for this is that it is possible, and even typical, for a text to fall into different categories in multiple ways. We therefore decided that the best way to approach this problem was to label contributions according to the dominant category they fell into (at least in our understanding of the text). If we wanted to do justice to every single text and its individual composition, however, we could not have worked on a corpus as large as ours. Moreover, we could not have made comparisons between magazines as objects consisting of different types of contributions, since we would have been lost in infinitely compartmentalised descriptions. The nature of taxonomy, as we can derive from the problematisation above, is necessarily reductive. Nevertheless, we decided to typologise the magazine contributions in our corpus to a very specific end and have therefore tailored this category to our specific research questions. The multi-genred contribution itself can be quite a complicated matter, as not all of its participation in different genres will necessarily be marked clearly as a straightforward and conscious switching between different types of text. Derrida himself operates with the complex example of La folie du jour by Maurice Blanchot, showing that this text plays with the different semantic layers of the word/genre ‘récit’, and ultimately refuses and provokes a generic ascription at the same time.

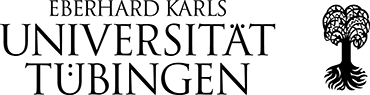

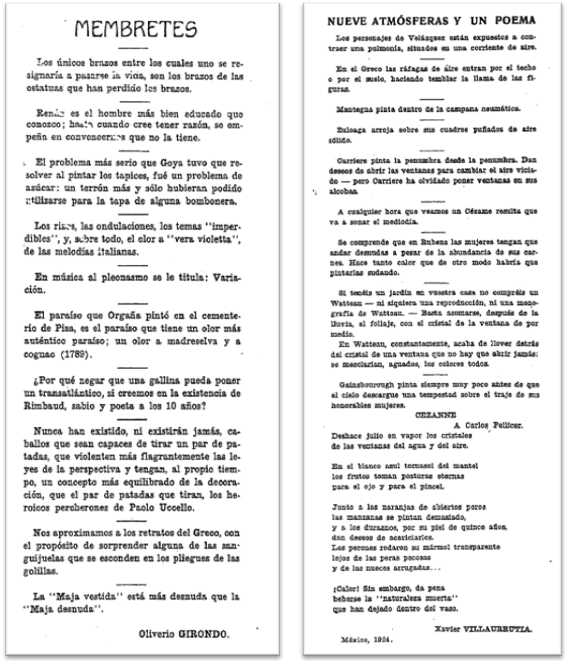

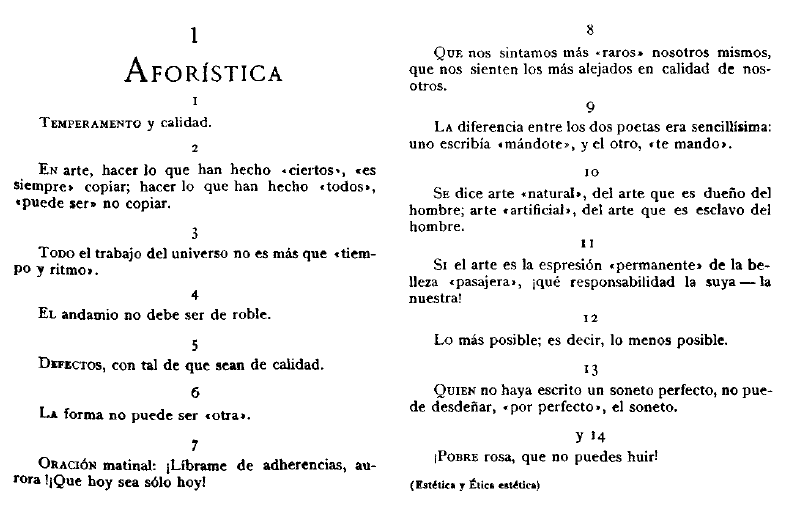

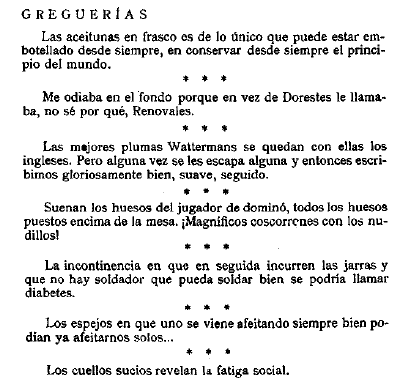

For example, the distinction between Lyricism and Non-fictional Prose can be rather problematic, particularly when it comes to small texts such as Xavier Villaurrutia’s ‘atmósferas’ and Olivero Girondo’s ‘membretes’ in Martín Fierro, or Juan Ramón Jiménez’s ‘aforística’ and Ramón Gómez de la Serna’s ‘greguería’ in Horizonte (Madrid) (fig. 1-3). Villaurrutia writes: ‘A qualquier hora que veamos un Cézame [sic] resulta qu[e] va a sonar el mediodia’ or ‘Gainsbourough pinta siempre muy poco antes de que el cielo descargue una tempestad sobre el traje de sus honorables mujeres’ (Villaurrutia: 3) and titles these lines ‘atmósferas’, aphorisms that have previously been compared to Oliverio Girondo’s ‘membretes’ (Corral: 456), of which the following are examples: ‘En música al pleonasmo se le titula Variación’, ‘Los únicos brazos entre los cuales uno se resignaría a pasarse la vida, son los brazos de las estatuas que han perdido los brazos’ (Girondo: 4). Both even turn to the same artist. ‘Nos aproximamos a los retratos del Greco, con el propósito de sorprender alguna de las sanguijuelas que se esconden en los pliegues de las golillas’ Girondo writes, while Villaurrutia remarks, ‘En el Greco las ráfagas de aire entran por el techo o por el suelo, haviendo [sic] temblar la llama de las figuras.’ Girondo’s ‘membretes’ have been described as strongly reminiscent of Ramón Gómez de la Serna’s ‘greguerías’ (Rössner: 240), with the latter having been widely published in the magazines of our corpus, including Horizonte (Madrid): ‘Los cuellos sucios revelan la fatiga social’; ‘Las mejores plumas Wattermans se quedan con ellas los ingleses. Pero alguna vez se les escapa alguna y entonces escribimos gloriosamente bien, suave, seguido.’ (Gómez de la Serna: 8). In the same issue of the Madrid-based magazine Juan Ramón Jiménez’ ‘aforística’ is published, which included gems such as: ‘EL andamio no debe ser de roble’, and ‘QUIEN no haya escrito un soneto perfecto, no puede desdeñar, «por perfecto», el soneto’ (Jiménez: 1). This becomes problematic because of the fact that the aphorism has been mostly described as Non-fictional Prose in the secondary literature (Schneider: 162). We have therefore allocated it to this category as well. ‘Greguerias’ and ‘membretes’, however, have been described as Lyricism, and we have proceeded in the same way. If there were no further information on those texts regarding the authors, or any paratextual clues, it would be hard to find differences in those texts considerable enough to argue convincingly that they are to be ascribed to different categories, while the difference between the ‘greguerias’ and ‘membretes’ and a sonnet, which end up being ascribed to the same ‘Type of Contribution’, are downright obvious. As we could not reinvent the wheel, the contradictions and overlaps of literary taxonomy and its resulting problems are again confronted in our data. And as we are handling thousands of texts, they become even more present and visible than in the regular day-to-day of literary scholarship.

Figure 1: Martín Fierro 8/9 and 12/13

Figure 2: Horizonte (Madrid) 3

Figure 3: Horizonte (Madrid) 3

The explanations so far have concentrated on the literary texts in the magazine. The principal idea behind our typology, however, was to create a form-based profile of the magazines as cultural and literary magazines. This evokes three spheres of perspective. The mediatic sphere, which puts a focus on the magazines as products pertaining to the larger literary press. The literary sphere, which views the magazines as literary objects in themselves, and which has been in the focus of this article so far. And the cultural sphere, which opens the magazines to other art forms, that find their representation in the magazines not only in textual but also, and importantly, in visual form.

In the mediatic perspective, our interest was focused on reflections of culture and literature. To this end, we established three categories: Review, Magazine Review, and Non-fictional Prose. This allowed us to see the interconnectedness of the magazines amongst themselves, and within the broader cultural and literary field. Non-fictional Prose, in contrast to the two other medium-specific categories, is a rather large category. It has been purposefully created that way, as it is supposed to show the participation of the magazine in a wider discourse, be this political, philosophical, cultural etc. It functions as a counterpoint to the literary categories, and sheds a light on the objectives of the magazine. The guiding principle was based on trying to answer the question of whether a magazine was created more as a platform and publishing outlet for young artists and writers than as a means of commenting, informing, and explaining the literary and cultural field to an interested public.

Next to the textual contributions, most magazines also feature a multitude of images, multi-modality being a characteristic feature of cultural magazines. We created an extra category for these, which contains all imagery in the magazines. Visual culture is an important aspect of the magazines. Some go without any images, while others do not only include a specific aesthetic, but even mark their poetic and artistic belonging, thereby creating their own visual language. Grecia would be an interesting example of this, as it indicates its transition from modernism to avant-garde on its front cover (fig. 5). It first shows a classical Greek statue, from issues 1 to 13. Issues 14 to 16 then features a traditional Greek amphora. From issue 17 onwards this amphora is accompanied by a motor oil can, marking a breaking point and referencing the avant-garde principle of innovation and acceleration. Interestingly, on the cover of issue 42 the magazine returns to featuring only the amphora, before, from issue 43 onwards, featuring images more akin to other avant-garde magazines. For example, it depicts Norah Borges’ wood engravings, a portrait of Isaac del Vando Villar, and a painting by Robert Delaunay.

Figure 5: Covers from Grecia

Other examples of the changing and developing visual culture in magazines would be Amauta indicating its connection to indigenous culture by including corresponding imagery, and Martín Fierro. Amauta manifested with its title its ‘adhesión a la Raza’ and its ‘homenaje al Incaismo’ (Mariátegui: 1), as ‘Amauta’ is a Quechua expression for wise men (Rössner: 247). The pre-colonial legacy presented in its first issue was prefigured visually by the cover picture of the head of a bronze-coloured Indian with an aquiline profile - an image that later became the hallmark of the publication. The inaugural cover was designed by the painter José Sabogal, artistic director of the magazine and responsible for most of the title pages. After a short sojourn in Mexico, Sabogal returned to Peru to strive for the creation of a revolutionary art in accordance with the new Peruvian spirit. He rebelled against European academism and his paintings, drawings and engravings became nurtured with ancient Inca richness. In consequence, the indigenous subject is not only present on the front covers but also appears on the inside pages, as Inca motifs depicting local flora and fauna or little scenes inspired by the traditional mates burilados – chiselled gourds – embellish the pages of the magazine.

A counterpoint to the ideologised, political and pro-indigenous magazine Amauta is Martín Fierro, which, lacking an indigenous legacy and political intention, may dedicate its title to the nation’s gaucho past, but sets the aesthetic and literary contents of the magazine firmly to other matters. The first issue of the periodical opens with the ‘Vuelta de Martín Fierro’, a column that defines its raison d'être. To the right of the short programmatic text, a cartoon of Martín Noel – mayor of Buenos Aires City – illustrates the ‘Balada del intendente de Buenos Aires’. In its initial editions, Martín Fierro relies heavily on the cartoonist Francisco Alberto Palomar (‘FAPA’) to illustrate its front pages, but in subsequent numbers shifts away from cartoons. The porteño periodical subsequently introduces a varied artistic repertoire, of national talents such as Norah Borges, Xul Solar, Emilio Pettoruti, José Fioravanti and Pablo Curatella), and of cosmopolitan big names such as Pablo Picasso, Georges Pierre Seurat, El Greco, Marc Chagall and Paul Gauguin.

The participation of contributions in multiple genre categories also pushes boundaries between the cultural -in this case visual-, mediatic, and literary spheres. Some of these cases can be even more problematic to decide, while at first glance seeming less of a difficulty than the multi-genred literary texts. Many questions arise from our corpus research, such as: What type in our model is a picture story, like the historieta ‘El barquillero y los pájaros’ (fig. 6) by Uruguayan artist Rafael Barradas? We have decided to assign it to the Image category, when at the same time it could also fall into the Fictional Prose category. (It was marked, however, by keeping the information on the language intact, with ‘Spanish’ noted in the respective column.) Where does the book review begin and where does the literary commentary end? Sometimes it is quite clear, while at other times it is a question of interpretation that is informed by the context and placement within a magazine. Is a list of ‘libros recibidos’ just a list, or does it have a function akin to a review? As this would lead to speculation regarding the motives of the magazines’ editors, we decided to sort such (and any) lists into Non-fictional Prose. Another more fundamental decision had to be made regarding autobiographical accounts, such as diary entries and travelogues. We decided to typologise them as Non-fictional Prose, despite an awareness of the long-standing debate (4) in literary studies on whether they are to be seen as fictional or non-fictional. Some texts prove to be more problematic and resistant to this decision-making process, and some categories are more prone to difficulties than others. The distinction between comments (as Non-fictional Prose) and reviews, for instance, is problematised by more frequent overlaps than that between Image and the text-based categories. Putting specific texts like short prose texts and lyrical prose texts, that are formally fairly close to each other into the categories, may require more interpretative work than simply allocating the fragment of a book of non-fiction and the fragment of a book of fiction.

Figure 6: Rafael Barradas. La Gaceta Literaria 58

What can be taken away from these reflections on typology and the practice of sorting contributions is that decisions are not only made when building a typological model, but are made with every labelling act. To be more precise, to mark a text as falling mostly into a specific category, is a question of interpretation and ultimately a decision. These interpretations and decisions are made with an awareness of the interdependency and overlaps that the contributions have with other categories, analogous to the rhizomatic network structures formed by historical genres (Hempfer: 29).

As we have tailored the categories to our research questions, they have been able to bring to light some interesting aspects of the magazines.(5) One of the central goals of this typology was to create a comparability between the magazine, which led to a necessity of more general categories, to which a broad spectrum of contributions could be ascribed. Being aware of the implications of categorisation, we decided on a typology of the magazine contributions in our corpus which would allow us to gain insights into the specific research questions that are of interest to us in this project. Those questions are concerned with the formal profiles of the magazines and their (self-)positioning in the literary field. It cannot be stressed enough, however, that these typological differentiations, and any statistical and visual explorations done on the basis of them, can only be the starting point for any research and no end in itself. They are only as valuable as the dialogue created by each researcher with the original material is rich and meaningful.

In the organizational chart below (fig. 7), the categories will be made more transparent, as they are broken down into a more detailed specification of contributions pertaining to each category. These groups are also, as categories are in general, typological interpretations in themselves, and could easily be ordered another way. We decided on grouping them in this way as it best served our uses. We make them visible to the public in this organizational chart to allow for a better understanding of our data, and to inform about the content that can be expected to be found when browsing our datasheets via these categories.

Figure 7: Contents of ‘Type of Contribution’

Bibliography:

Barradas, Rafael. ‘Historieta póstuma de BARRADAS. El barquillero y los pájaros.’ In: La Gaceta Literaria, No. 58 (1929). 5.

Bowker, Geoffrey C., and Susan Leigh Star. Sorting Things Out. Classification and Its Consequences. Cambridge, MA / London, England: The MIT Press, 1999.

Corral, Rose. ‘Notas sobre Oliverio Girondo en México. Introducción a un texto de Xavier Villaurrutia y la correspondencia Reyes/Girondo.’ In: Raúl Antelo (Ed.). Olivero Girondo. Obra completa. Madrid et al.: ALLCA XX, 1999. 454-474.

Derrida, Jacques. ‘The law of genre.’ In: Critical Inquiry, Vol.7, No.1, On Narrative (1980). 55-81.

Fricke, Harald. ‚Definitionen und Begriffsformen.‘ In: Rüdiger Zymner (Ed.). Handbuch Gattungstheorie. Stuttgart: Metzler, 2010. 7-10.

Frow, John. Genre. Oxon / New York: Routledge, 2015.

Girondo, Oliverio. ‘Membretes.’ In: Martín Fierro, No. 8/9 (1924). 4.

Gómez de la Serna, Ramón. ‘Ramonismo. Greguerías.”’In: Horizonte. Arte, Literatura, Crítica, No. 3 (1922). 8.

Hempfer, Klaus W. ‚Zum begrifflichen Status der Gattungsbegriffe: Von ‚Klassen‘ zu “Familienähnlichkeiten“ und “Prototypen.“‘ In: Zeitschrift für französische Sprache und Literatur, Vol. 120, No. 1 (2010). 14-32.

Jiménez, Juan Ramón. ‘Poesía. (La flor más alta). 1. Aforística.’ In: Horizonte. Arte, Literatura, Crítica, No. 3 (1922). 1.

Lehmann, Christian. ‘Typ und Typologie.’

<https://www.christianlehmann.eu/ling/typ/index.html?https://www.christia... [last accessed 11 August 2020]

Mariátegui, José Carlos. ‘Presentación de Amauta.’ In: Amauta, No. 1 (1926). 1.

Müller, Ralph. ‘Kategorisieren.‘ In: Rüdiger Zymner (Ed.). Handbuch Gattungstheorie. Stuttgart: Metzler, 2010. 21-23.

Rössner, Michael (Ed.). Lateinamerikanische Literaturgeschichte. 3rd edition. Stuttgart: Metzler, 2007.

Schneider, Ulrike. ‘Zu Einigen Grundproblemen Neuerer Aphorismusforschung.‘ In: Zeitschrift für französische Sprache und Literatur, Vol. 112, No.2 (2002). 155-169.

Villaurrutia, Xavier. ’Nueve atmósferas y un poema.’ In: Martín Fierro, No. 12/13 (1924). 3.

(1) ‘sich Überblick und Ordnung in der Vielfalt von Phänomenen eines Objektbereichs zu verschaffen’ (Lehmann)

(2) All translations: Teresa Herzgsell

(3) These genres can be traced back to Plato and Aristotle. However, not without difficulty, as Plato solely reflected on narratives (epic, dramatic, dithyramb), and Aristotle's Poetics ‘deals only with tragedy and epic’ (Frow: 62). As Frow illustrates, there is a slow historical process that shifts the description from the Platonic and Aristotelian modes of speech to the introduction of genres. This shift allowed the inclusion of lyricism next to drama and epic as a third genre (Frow: 61 ff.).

(4) For a summary of this debate see Martina Wagner-Egelhaaf‘s, Autobiographie (2005).

(5) For further reading consult: Teresa Herzgsell ‘Transkontinentale mediale Netzwerke: Perspektiven datenbasierten Arbeitens in der Zeitschriftenforschung’. In: Mark Minnes, Natasche Rempel (Eds.) Netzwerke – Werknetze. Transareale Perspektiven auf relationale Ästhetiken, Akteure und Medien (1910-1989). Hildesheim New York: Olms, 2021 (POINTE 20).

A PDF of this article can be downloaded from the DARIAH repository. (https://repository.de.dariah.eu/1.0/dhcrud/21.11113/0000-000D-1D07-C)