Teresa Herzgsell: Genre distribution and Fictional Prose in the Magazines of the Avant-Garde

When looking at all 19248 contributions across the avant-garde magazines of the corpus of the project ‘Literarische Modernisierungsprozesse und transnationale Netzwerkbildung im Medium der Kulturzeitschrift: vom ‘Modernismo’ zur Avantgarde’ in their totality, we can see, as this graphic illustrates, that there is a clear preponderance of Non-fictional Prose texts, with such texts making up almost half of all contributions.

Figure 1:Genre distribution in all 23 avant-garde magazines

Together with the two other not primarily literary text types in the categories – Review and Magazine Review – this suggests that the magazines investigated by the project are not necessarily focused on the publication of artistic and literary production itself and that they provide less of a place for publication of such material and more of a space for discussion and accompanying commentary. This is not the case, however, and it is once more an indicator of the challenges posed by statistical values and diagrams, as they need to be read with caution and require either extensive knowledge of the subject matter or careful description of the data used. A contextualization brought together with other values that creates a dialogue within the data-explorations, aimed at understanding and interpretation, and not just stating singular facts, is better equipped to give insights into the corpus. When the data behind this diagram is pulled apart and the single magazines are looked at, it becomes clear that the surplus of Non-fictional Prose is created mostly by the larger publications (1), such as La Gaceta Literaria, Claridad, Revista de Avance, and Amauta, which all have more than a thousand contributions and shift the values in favor of this type of contribution.

This genre distribution, therefore, is not indicative of all the magazines investigated. In particular, smaller magazines often had another publishing programme, and sometimes almost exclusively focused on the publication of literary – mostly lyrical – texts. This phenomenon can be seen in the table below, in which all avant-garde publications included in the project are listed and the distribution of genres in each title are indicated. The highest value per magazine title is marked red, and the last line gives the average percentage of the respective type of contribution across all of the magazines in the study. This allows for a comparison of each magazine’s values, and shows that, when size differences are eliminated (as only the percentages and not the total numbers are used for this average), this results in a different picture of this part of the project corpus.

Table 1: Genre distribution per magazine title (2)

What is noteworthy is not only the range of genre distribution seen across the avant-garde magazines, but also the fact that on average Lyricism and not Non-fictional Prose proves to be the text type most frequently included in the magazines. While larger publications tend to lean more towards the latter, the smaller publications, such as Irradiador, Favorables Paris Poema, and Reflector, tend to publish mostly Lyricism and function as poetry outlets for certain literary movements and groups. Horizonte (Madrid), for example, is one of the most important Ultraist magazines, Irradiador is closely linked with Mexican Stridentism, and Boletín and Editorial Titikaka are publications of the ‘Orkopata’ group in Peru, to name just a few.

Carmen is the magazine most dedicated to the publication of Lyricism, and the most extreme in terms of genre distribution, as there are only contributions pertaining to the genres of Non-fictional Prose and Lyricism; it marks the beginning of a new era in Spain, with the emergence of a group, not uncontestedly one might point out, termed the ‘Generación del 27’, whose central protagonists will later go on to become some of the most famous lyrical authors of 20th-century Spain. The magazine was founded by Gerardo Diego, one of the best-known Spanish poets to date, and an important figure of this group. As the founding article of Carmen states ‘No le apasiona más que la poesía, aunque extiende su atención a todas las formas de arte, que ella ve como cifras—metamorfosis o versiones en extraños lenguajes—de oscuros ímpetus poéticos’ (Carmen: 1), declaring its devotion to poetic forms of expression, which is mirrored in the data collected.

While lyricism and its developments have been studied quite extensively for the Spanish-language avant-garde movements, other types of literary writing have not received the same attention. The data nevertheless points to those types of texts as present in the corpus despite their smaller numbers, making it impossible not to address them. The following paragraphs will take a closer look at Fictional Prose across the whole corpus. In avant-garde studies, fictional prose writing has habitually been pushed aside in favour of the more attention-demanding and daring outputs in lyricism, performances, manifestos, and the visual arts. This has already been called for, for example by Mechthild Albert, who reacted by dedicating a monography to vanguard prose in the late 1990s (cp. Albert: 1). As Pöppel has pointed out, the 1990s and early 2000s saw a small hype towards vanguard narrative production (cp. Pöppel: 189), however, this trend seems not to have caught on on a larger scale. Despite the existence of some publications dedicated to the topic, interest in vanguard prose still falls short in comparison to the investigation of other writing, especially poetry writing, as cursory searches in library catalogues easily show.

In the project, it was decided that Fictional Prose should be given a category of its own, alongside Drama and Lyricism, despite the problems that this would entail. As has been pointed out, avant-garde writings to a great extent reject the allocation of textual definition and actively dissolve genre limitations. Mechthild Albert stresses that even the vanguard novel causes confusion in genre allocation with the ‘lyrical character of the narrative prose and the trivial nature of its contents. The summation of these aspects, lays bare the puzzlement of current criticism in view of the hybridity of a literary form, breaking away from conventional genre norms’ (3) (Albert: 121). Or, as Carlos Ferreiro González writes, it can be considered ‘esencial para la comprensión de los movimientos artísticos vanguardistas, la interacción de los distintos géneros y la dislocación de las férreas estructuras formales y temáticas que consideraban a los moldes de la creación literarios como compartimentos estancos [...]’ (Ferreiro González: 109). In order to gain insights into the production and composition of the magazines under study, the project’s researchers decided to persist in separating the texts into these classical categories (see Teresa Herzgsell Categorization as Theory and Practice). This decision was to allow a selective look at literary prose writing, an often-neglected aspect of the avant-garde, both in this article and in follow-up work with the data. This categorization also had the practical effect of making this type of writing more visible, as with the data-driven approach these texts cannot be ignored so easily.

As the boundaries between genres became blurred during the avant-garde era, it is instructive to provide a brief specification of the types of texts that were put in this category. As with other categorizations, clues in paratextual comments were taken as indicators. The magazines every so often inform the readers of a text’s generic allocation, marking it as a ‘cuento’ in the subtitles. Prominent examples for this can be found in the Gaceta Literaria, where often the location of the text’s origin is given at the same time, when the magazine substitutes titles with phrases like ‘”cuento ruso”, “cuento judío”, “cuentos americanos”’, etc. What is also made known quite often is that texts are fragments of a novel or excerpts from a story collection, and this is indicated to the reader by means of additional titles, notes below the contributions, short accompanying commentary etc. These paratextual elements make it rather easy to categorize such contributions, while other text allocations to the category are much harder to decide upon, especially when it comes to very short texts that lean heavily on lyrical writing styles. A frequent example of this are the short texts Ramón Gómez de la Serna publishes under the umbrella-term Ramonismo, that are sometimes only distinguishable from his Greguerias (which are generally considered lyricism) by paratext. In case of doubt and where there is no paratextual hint, categorization comes down to interpretation and the viewpoint of the person collecting the data. As a general guideline what was looked at were markers such as the use of tense, the existence of narrative structures such as narrator and narrated time and place, forms of narrative development and movement in the narrated space, and obviously an ex-negativo approach which checks for markers that would point to other types of texts (mostly lyricism), such as the conscious use of formalities in line usage and cross references within the text. All of these, admittedly quite varied, forms were included in the category Fictional Prose, which will become the focal point of the following examinations of a transatlantic Fictional Prose network forming through the magazines.

The network visualizations below illustrate this segment of the project data. A first finding is the relatively small group of 19 authors who have had their fictional writings published in Europe and Hispanic America, as can be read from the geo-mapped network. It consists of Alfonso Hernández-Catá, Pierre Louys, Benjamín Jarnés, César Vallejo, Ramón Gómez de la Serna, Isaak Babel, Mariano Azuela, Leo Tolstoy, Eduardo Mallea, Luis Cardoza y Aragón, Jaime Ibarra, Massimo Bontempelli, Jules Supervielle, James Joyce, Joseph Delteil, Ernesto Giménez Caballero, Lino Novás Calvo, Anatole France, and Juan Chabás.

![Figure 2: 41 Contributors to the genre ‘Fictional Prose’ (only those contributing to more than one magazine) [visualisation Jörg Lehmann]. Figure 2: 41 Contributors to the genre ‘Fictional Prose’ (only those contributing to more than one magazine) [visualisation Jörg Lehmann].](https://www.revistas-culturales.de/sites/default/files/fictional_prose-map.png)

Figure 2: 41 Contributors to the genre ‘Fictional Prose’ (only those contributing to more than one magazine) [visualisation Jörg Lehmann].

The second visualization draws more attention to the magazines as a medial network, and less to their geo-location. It makes apparent what has been thematized above, that larger publications threaten to outshine the smaller ones, as their sheer numbers eclipse the others visually. What the network achieves, however, is once again a focus on a smaller group of authors that were formal connectors and ready to be received through the magazines in more medial locations through their fictional writing. (5) The largest group (329 authors) of the 370 Fictional Prose authors contributed to one publication exclusively. Most of those 329 authors published only one text (254 authors) in the respective publication; much fewer published two (36), three (21), four (9) or five (6) texts. The three most prolific authors contributing to only one magazine are Juanita Pueblo, with eleven texts in Claridad, María Wiesse, with six texts in Amauta, and Estuardo Núñez, similarly with six texts in Amauta. Accordingly, a higher number of contributions does not necessarily correlate with a wide dissemination of these texts, even less so does it correlate with cross-Atlantic publication. While the two authors with the most Fictional Prose contributions – Ramón Gómez de la Serna (83 Fictional Prose contributions in 8 magazines; 2 Hispanic America / 6 Europe) and Benjamín Jarnés (14 contributions in 7 magazines (6); 4 Hispanic America / 3 Europe) - are published transatlantically, the publications of the two authors that follow – Arturo Pablo Peralta Miranda (pseudonym Gamaliel Churata; 11 contributions), and Juanita Pueblo (also 11 contributions) – remain within the confines of Hispanic America. The same observation can be made across all contributors. Of the 19 transatlantically published contributors, nine (7) are responsible for three, and five (8) for two texts. The remaining three authors in the transatlantically published group all provide fewer contributions than the three most prolific who were printed in only one magazine: Mexican author Mariano Azuela places 7 texts with 4 magazines (Amauta, Contemporáneos, La Gaceta Literaria and Revista de Avance), Spaniard Jaime Ibarra with his 6 Fictional Prose texts is present in 4 magazines (Contemporáneos, La Gaceta Literaria, Martín Fierro, and Ultra) as well with 6 texts, and lastly Guatemalan Luis Cardoza y Aragón 4 texts were printed in 3 magazines (Contemporáneos, La Gaceta Literaria, and Revista de Avance).

When looking at the nodes of the magazines in the network below, a correlation can be seen between magazine size and connectedness. Larger publications like the Gaceta Literaria and Revista de Avance, but also medium sized ones like Contemporáneos and Martín Fierro tend to publish more Fictional Prose altogether and therefore are also better connected. At the same time, it is not only size that matters in this context, as the example of Claridad shows. More of a political magazine, it shares less connections with the other magazines, because its agenda is not predominantly driven by aesthetics but more by ideology, as the publishing of Tolstoy and Rafael Barrett underlines. A similar observation can be made with Peruvian Amauta. The well-connected magazines mentioned are definitely more interested in a cultural and literary exchange out of a desire to promulgate literary development, and therefore share authors that provide achievements in that regard.

Figure 3: Fictional Prose Network

In order to enlarge these genre-specific observations towards a general idea of the transferral activity of the Fictional Prose authors, the Transatlantic Transfer Rate can be used. A number that is calculated in the project by dividing the number of publications (regardless of genre) of an author (or magazine) outside of her or his continent of origin by the overall number of her or his contributions. As per the Transatlantic Transfer Rate of the 287 authors of Fictional Prose, for whom the calculation of this rate was possible (9), 175 contributors were only published in magazines from the continent on which they were born, while 71 were published inside and outside of their birth-continents, and 41 were published only outside of them. (10) This rate is to give some background as to a transferral activity that is left out by only looking at these two genre-focused visualizations. There is, however, also transferral activity through literary fiction alone, as the networks show, and as it is not necessarily where one would typically assume it to be it does deserve some attention. In order to compare this transferral activity within the genre of Fictional Prose alone it suggested itself to calculate a secondary Transatlantic Transfer Rate based only on the contributions of Fictional Prose.

The numbers received by this adaption reduce the group showing transferral activity, while the other two groups are enlarged. As has been discussed above, 19 authors were published on both sides of the Atlantic with their Fictional Prose. These are significantly fewer contributors than the 71 produced by the calculation of the general Transatlantic Transfer Rate. Both other groups score increased numbers. With Fictional Prose only 51 authors are published outside of their birth continent, while 212 are published solely inside of it. This does suggest that this genre is not one that allows for a lot of permeability and is not a door opener in other literary contexts. This makes it even more important to look at the figures who were able to place their literary fiction in several magazines on both sides of the Atlantic.

As has been argued above, frequency does not play a significant role in transatlantic publishing. Nor does literary impact, as the example of Jorge Luis Borges suggests. When one thinks of small fictional forms in the Spanish-language literature of the 20th century, his name inevitably emerges. In the Fictional Prose networks of the magazines, however, he only plays a marginal role, remaining with his fiction in the Hispanic-American sphere. This can be explained by the fact that Borges rose to fame as one of the world's most celebrated short fiction writers only after the period of his appearance in these magazines. In the 1920s he predominantly published poetry and essays and his most famous story collections Ficciones and El Aleph did not appear until the 1940s. Ergo his role as a fiction writer is rather small in the magazines, and will come as no surprise to Borges aficionados.

That Ramón Gómez de la Serna is the most frequent contributor in the category of Fictional Prose is no surprise, as he is a well-established figure of Spanish literary history far beyond the avant-garde research community. His impact could be felt just as strongly during the time of the vanguard movements, and his style of writing found many imitators and individualized interpretations, for example with Oliverio Girondo’s ‘membretes’ (see Teresa Herzgsell Categorization as Theory and Practice). While the egocentric character of his poetic programme as a ‘vanguardia unipersonal’ prohibited the founding of a vanguard movement, his own writing was made available to many readers through the magazines of the avant-garde. Perhaps one reason for this accessibility, apart from an innovative style of writing and self-portrayal which concorded perfectly with the spirit of new movements at this time, is the shortness of most of his texts. His fiction is so close to lyricism not only in style but also in size that it lends itself well to the magazine publishing form, that due to its collage-like nature is prone to advancing short over long forms. What is also interesting in the case of Ramón Gómez de la Serna, is the fact that it is only in the Argentinian magazines Martín Fierro and Proa that his Fictional Prose texts were published. (11) Therefore, the transposition of his texts to Latin America is to be best read in terms of his elaborate positioning within the Ultraist movement as an early Spanish-language vanguard figure. In this context, his writing was considered innovative in a vanguard sense and, perhaps more importantly, functioned as an example and proof of an innovative tradition within this language area. It is in this sense a marked effort by the creators of the magazines to emancipate themselves from the dominant vanguard currents of France, Italy and Switzerland.

Fictional Prose contributions by other well-known authors can be understood as an achievement and effort by the magazines to include examples of literary writings from the other continent. Mariano Azuela, for example, while being the third most frequent contributor, is an established figure of Mexican literary history, a status reflected in his fictional contributions, which are almost exclusively samples from his novels. His only publication in Spain, in the Gaceta Literaria, is a chapter from his most famous book Los de abajo. Comparable to Azuela are the literary status and contributions of Guatemalan writer Luis Cardoza y Aragón. His contributions are all fragments from his novel Torre de Babel, except for ‘Hombre-Sandwich’, a self-proclaimed ‘relato surrealista’ first published in El Imparcial and reprinted later without indication of any prior publication in the Madrilenian gazette.

A more interesting case from a literary historical perspective is that of Benjamin Jarnés, who even today remains one of the lesser-known figures (and is in comparison to the aforementioned authors virtually unknown). While not being completely forgotten - he has been the subject of several monographs - sources such as his corresponding entry in the Encyclopedia Britannica point squarely to Jarné’s secondary positioning in Spanish literary history. The Britannica posits as a reason for this situation the fact that Jarnés, like many other supporters of the Second Republic, went into exile after its defeat. In Mexico he was quite active as a writer but he went back to Spain in the 50s. The perception of him by literary historians in Mexico as well as in Spain might therefore be that of an Other, hard to pinpoint to a nation and not really belonging to any. The data forms a corrective to this, immediately highlighting him as one of the most productive Fictional Prose authors in the magazine corpus, while being widely received as well. This is underlined by Juan José Lanz who writes: ‘Cuando el 18 de julio de 1936 se produce el alzamiento de las tropas rebeldes y estalla la guerra civil, Benjamín Jarnés es ya un escritor consagrado o, al menos, a punto de consagrarse’ (Lanz: 134). This process was interrupted by the war and his exile and led to the marginalization of an author on the verge of canonization, as Lanz describes his devaluation by Spanish critics in the following decades (cp. Lanz: 135 ff.). Manuel Bonet, who does include him in his very extensive Diccionario de las Vanguardias, also mentions those attacks and devaluations of his writing by the Spanish critics (cp. Bonet: 151). His initial fame is clearly mirrored in the magazines, where he is featured across the ocean in Martín Fierro, Proa, Contemporáneos, and Revista de Avance, even before his exile began in 1939. His role can be seen as a transatlantic one with regard to Fictional Literature not only because his production was located on both continents but also, even more pertinently, because he was published and read on both.

Even less is known of Jaime Ibarra. Internet sources are sparse and inconclusive, and the entry on him in Bontes Diccionario de las Vanguardias provides only little information, focusing on his inclusion in magazines and his participation in the Ultraist movement (cp. Bonet: 342). The texts he publishes in the magazines are, similar to Jarnés, individual short prose texts well-suited for publication in these magazines. Apart from personal history it becomes clear that vanguard writers of Fictional Prose are less likely to receive attention by scholars later on, specifically because of the reasons mentioned before that favor Lyricism as the number one vanguard genre. This disregard is aggravated by the focus many researchers put on the concept of literary generations, as Eduardo Gregori and Juan Herrero-Senés point out: ‘In sum, traditional Spanish literary history marginalized the narrative production of the 1920s under layers of artificially-constructed “generations” that precluded any comparatist understanding of Spanish modernism’ (Gregorio/Herrero-Senés: 2).

The authors discussed so far, are the most prolific ones in this genre with four or more contributions of Fictional Prose. For the rest of the transcontinentally published authors to the genre, a cursory view must suffice. What is conspicuous is the inclusion of the same foreign authors both in Latin America and Spain, such as Anatole France, Leo Tolstoy, Joseph Delteil, Massimo Bontempelli, Isaak Babel, Pierre Louys and James Joyce. These represent half of the authors in the remaining group of transatlantically published writers with 3 or less contributions. The rest are in the majority Latin American authors. Another observation that can be made, in context with what has been pointed out about Benjamín Jarnés, is that while migration is obviously beneficial when it comes to the promulgation of publications, it is a hindering factor for the inscription of an individual into literary history, as the literary historical writing on other figures with migratory histories, such as Jules Supervielle and Juan Chabás, similarly suggests.

Focusing on Fictional Prose in the magazines of the avant-garde, in conclusion, permits us a critical reevaluation of the literary scholarship around literary history and the treatment of vanguard text-production. Not only are certain types of texts widely neglected, but certain authors fall back in the attention literary history awards them, simply because they contribute to the ‘wrong’ genre or because they migrate and their cultural belonging is thereby complicated. This short overview of the magazine material has shown that there is a whole field awaiting exploration and that the way this is laid open to future researchers is by looking at and interpreting metadata.

Bibliography:

Lanz, Juan José. ‘La novelística de Benjamín Jarnés en el primer exilio: Hacia la novia del viento.’ In: Bulletin hispanique No. 102-1 (2000). 133-167.

britannica.com. ‘Benjamín Jarnés’. <<https://www.britannica.com/biography/Benjamin-Jarnes>> [last accessed 11 August 2020].

Bonet, Manuel. Diccionario de las Vanguardias. Madrid: Alianza, 2007.

Diego, Gerardo. ‘1.‘ In: Carmen 1 (1927).

Albert, Mechthild. Avantgarde und Faschismus. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter, 2017.

Ferreiro González, Carlos. La prosa narrativa de vanguardia en Chile (thesis doctoral). 2006.

Pöppel, Hubert. ‘Nuevos estudios sobre las vanguardias en América Latina.’ In: Iberoamericana a. 9 no. 35 (2009). 189-202.

Gregorio, Eduardo and Juan Herrero-Senés. Avant-Garde Cultural Practices in Spain (1914-1936): The Challenge of Modernity. Leiden/ Boston: Brill, Rodopi, 2016.

(1) ‘Larger’ in this case refers to the numbers of contributions caused by longer publishing periods, more or bigger issues, etc.

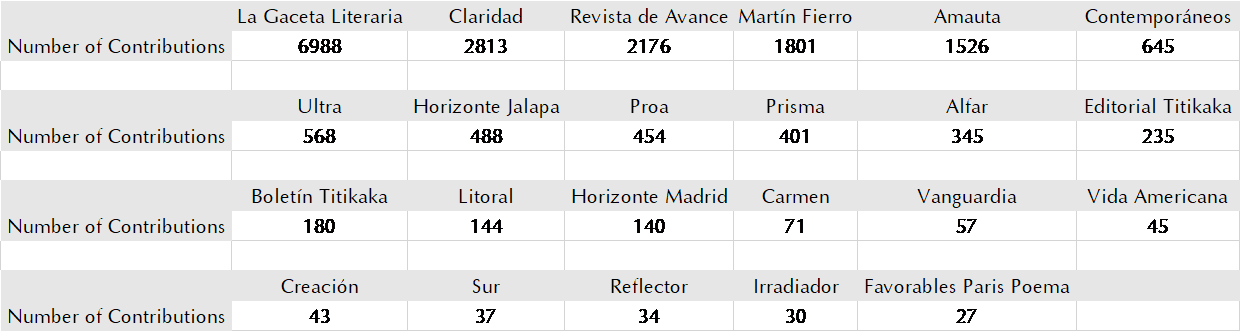

This table demonstrates the huge differences in numerical size as it gives the number of contributions per magazine:

(2) There are two problematic values in this table, as should be noted. For Claridad the category ‘Image’ has not been collected for the project out of time restraints. Everyone familiar with Claridad will notice this discrepancy immediately as the images in this magazine speak volumes of its political outlook. Moreover, the contents for this magazine have not been collected fully. The data that has been collected spans the period from July 1926 to December 1930, or the issues 1 to 221. As it is one of the larger magazines of this period and its publication of Fictional Prose exceeds the average value, it is included in this article.

For the same reason Alfar is also taken into account, despite the data collection covering only one year (September 1923 to September 1924), during which time the magazine was published in La Coruña, Galicia. In 1929 the magazine moved its publication place to Montevideo, Uruguay. For this period there has been no data collected in the project, which is why it is considered part of the Spanish literary field in the study.

(3) ‚der lyrische Charakter der narrativen Prosa und deren inhaltlich Belanglosigkeit. Die Summierung dieser Aspekte verrät die Ratlosigkeit der zeitgenössischen Kritik angesichts der Hybridität einer literarischen Form, die mit dem herkömmlichen Gattungsschema bricht.‘

(4) All translations: Teresa Herzgsell.

(5) In order to make the network more readable only the names of these authors that contribute to more than one magazine were included. The rest was kept as non-labeled nodes. Most contributors were published in one magazine alone and, in many cases, only once.

(6) This staggeringly high number in comparison with the other contributors is due to the fact that most of those texts by Ramón Gómez de la Serna are very small, condensed narrative images, in size rarely larger than a regular poem.

(7) Massimo Bontempelli, Juan Chabás, Eduardo Mallea, Jules Supervielle, Isaak Babel, Ernesto Giménez Caballero, Alfonso Hernández-Catá, James Joyce, and Pierre Louys.

(8) Joseph Delteil, Anatole France, Lino Novás Calvo, Leo Tolstoy, and César Vallejo. They are all published with one text in Europe and one in Latin America.

(9) The discrepancy between this number and the total of 370 Fictional Prose writers stems from not being able to find a country of origin for the remaining 83 of them.

(10) This is not visible in the networks included in this article for two reasons. First, the networks focus on Fictional Prose only. As the values for the Transatlantic Transfer Rate include all contributions of those authors it is possible that they published little to no Fictional Prose in the foreign as well as the continental markets. Second, a lot of contributors only published to one magazine, which renders them a non-labeled node.

(11) When looking at the other genres which include Ramón Gómez de la Serna, it shows that his reach in America is not much larger than that. There are two more magazines that both publish a short Non-fictional commentary note by him: Revista de Avance and Editorial Titikaka. His literary work stays within the confines of Europe and Argentina.

A PDF of this article can be downloaded from the DARIAH repository. (https://repository.de.dariah.eu/1.0/dhcrud/21.11113/0000-000D-1D0A-9)